The ‘generation gap’ of the 1960s and ‘70s was all about parents and children. A schism developed because of the post-war shift in values and attitudes, leading to anger and misunderstanding. As Roger Daltrey of The Who so memorably put it, on behalf of the youngsters of his day, ‘why don’t you all f-f-f-fade away?’ Nearly sixty years on, in the advanced industrialised economies, many people are working longer and retiring much later in life than in previous generations. The age gap between those entering the workforce and those leaving it is wider than ever. And The Who are on tour again!

Nobody wants to see ‘generation gap’ bust-ups in the workplace, and in any case we can’t afford them, given everything else that’s going on. Businesses need to find ways to recruit, and work with, people from all generations, recognising their different needs and contributions.

This Collaborative Conversation is hosted by GW+Co Head of Design Lindsay Cast, who sat down with two colleagues to discuss work culture – specifically, how different generations work together…

“People try to put us down… (talkin’ about my generation)”

Lindsay: Hello and welcome to another conversation in our transformation series. I’m joined by two GW+Co team members who come at things from different points on the generational spectrum, Michelle Chow, who can be described as a Millennial, and Esther Compostella, who’s a Baby Boomer. What do you see as the key differences between the two generations, if any?

Esther: For me, it’s more about individuals than generations. Each generation consists of a multitude of unique individuals with their own opinions, values, behaviours and plans for the future. So, stereotyping generations doesn’t feel right. It’s too easy to use generational stereotypes to put people into different buckets, and it’s also limiting in terms of others’ expectations and even your own mindset. The differences between people only come from the generation they are born into to a certain degree – I believe it’s more about the individual, their personality and upbringing. For example, I know some Millennials who show many stereotypical characteristics of a Baby Boomer like me, because of their upbringing. Things like being focused, goal-oriented and hard- working, and they talk less about work-life balance, values, entitlement, in the way that stereotypes of Millenials suggest. However, cultural experiences can be associated with the times into which a generation is born, and of course we’re all affected by societal, economical and political trends.

Lindsay: Michelle, would you agree that when we say Millennial, Baby Boomer, Generation X, really we’re just talking about timeframes, and that the differences are purely down to individuals?

Michelle: Not necessarily, but I agree with Esther that there are a lot of similarities between generations. However, I do think there are differences as well, in that attitudes, values, and beliefs have changed.

Esther: Surely, though, Baby Boomers, Millennials, whatever, are just marketing terms. They’re useful when people want to describe personas as a way of understanding marketing demographics, but I’d rather say ‘younger generation’ and ‘older generation’ because the extremes in values and behaviours are between older people and younger people in the workforce. And I think the main differences are caused by technology. Millennials are used to Googling everything, having all the information at their fingertips. It makes them ‘experts’ immediately, they’re very quick to pick things up. People in older generations tend to move slower. But while we may not be as quick with technology, I think we bring insight and experience to the table, which Google can’t give you.

Michelle: I might be slightly biased here, but I do think Millennials champion issues such as mental health and diversity and inclusion in a way that makes them different from previous generations. We’ve realised that race has nothing to do with how well someone can perform at work. As a person of colour, I have experienced racism, but I’m only 26 and I know, and can imagine, that racism was much worse in the past. Now that people are putting more focus on culture, we’re working together towards what’s important, based on the understanding that having people of different races working together is an advantage. That’s what I’m trying to achieve.

Lindsay: Would you say that you entered a workforce which is more aware of certain ideas, and places different importance on things to, say, when Esther joined the workforce?

Michelle: I think so. I think every generation introduces something new to focus on, in a way.

Esther: I agree, the world constantly evolves. When I was younger, basic civil rights was an important topic, it was at the start of those developments. Now we talk about DE&I in the workplace, and this is just the beginning of further cultural and societal developments. Hopefully, this will no longer be ‘a topic’, it will be a day-to-day business reality.

“Just because we get around… (talkin’ about my generation)”

Lindsay: So far, you’ve identified technology, particularly the way we access information, and awareness of social issues as key differences between generations. Are there other differences that stand out?

Michelle: I think work-life balance, and aspirations at work, and embracing culture and purpose, the vision of the company. I think younger people find those things really important. For example, someone who really cares about the environment and sustainability will choose a career that matches their values.

Esther: I think whether someone cares about such things depends on the individual. You could be a Millennial, or a Baby Boomer, or Generation X – or, better, an older or younger person – because we all want work-life balance. I still want to fulfill my potential and keep learning, both at work and outside of work.

Lindsay: Would you say the things that you look for in an employer have changed since you first entered the workforce?

Esther: Yes, because of the stage I am at in my life. Having had an interesting career, what I value has shifted slightly. However, even when I was younger, I wouldn’t have just done anything, or worked with any type of client, to win income or help me shine. That has not changed.

Michelle: I think how people are hired and how they decide to leave has changed. Nowadays, people have more freedom to say, ‘Look, if I don’t align with this place, if it isn’t right for me, I can sidestep into another career, another sector’.

Esther: I would agree with that. When I started my working life I was conscious of the need to have a seamless CV, without gaps, always building on what I’d been doing before. Today, it is much more acceptable – even desirable – to have a broader palette of experiences.

Lindsay: Businesses need to bridge these generation gaps. From your perspective, how can they do that?

Michelle: Companies need to articulate their culture and purpose, and be true to it in their actions, to attract younger talent.

Esther: I think businesses should assume less, and communicate more. We tend to assume that because someone is younger or older, they will behave in a certain way. But we shouldn’t pigeonhole people like that. We all have individual strengths and weaknesses and expectations and needs, whatever generation we’re supposed to be.

Michelle: I just want to add to that I agree on the question of assumptions, because that’s a massive barrier.

Esther: Businesses need to leverage the wisdom of experience, but also make use of the fresh perspectives and energy of every emerging generation. If you can combine them, it can be very powerful. People should learn from each other, and be open. We could even turn the tables in things like mentoring. Michelle could be mentoring me, rather than me mentoring Michelle. That kind of ‘reverse mentoring’ is an amazing idea, it can transform workplace relationships and have a positive impact on business results. Maybe not everyone would be up for it, but I think it’s worth trying.

Lindsay: So it’s about understanding and valuing the different types of contribution that people can make…

Esther: …and not focusing on ourselves all the time. It’s difficult to find common ground if we’re only focused on ourselves. We need to keep an open mind. And, as Michelle said, there are some very smart young people out there, and businesses benefit from the diversity of thought that can come from people of different ages.

“My generation…”

Lindsay: We work closely with the engineering and manufacturing sector in the UK, which seems to have a problem bridging this gap. Why do you think that is and what can they do about it?

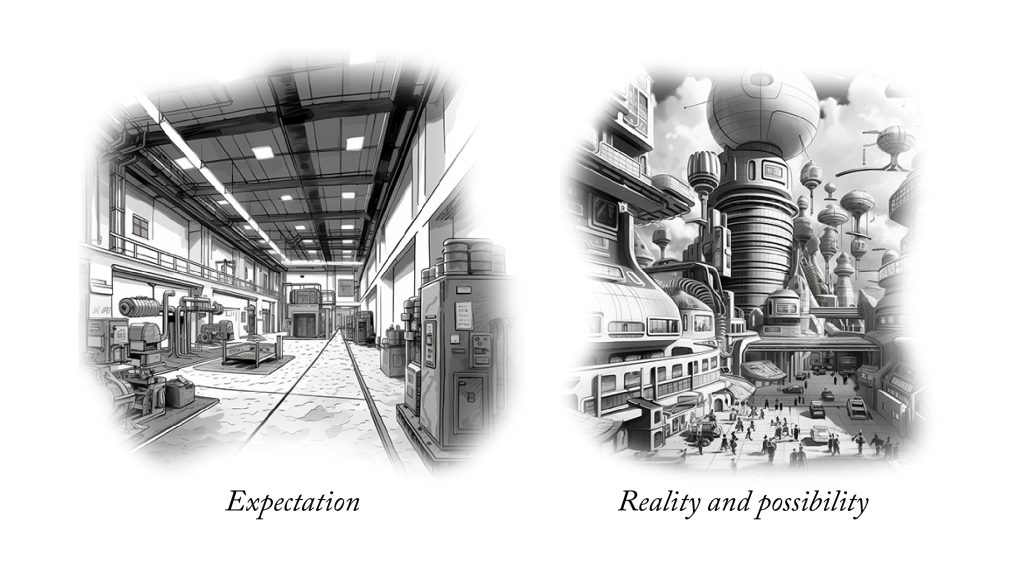

Michelle: There’s a lack of clarity about why starting a career in the manufacturing sector is a good idea. Manufacturing businesses are very much B2B, they’re not seen as much on social media, or known by most people. Fundamentally, it’s an image issue. Engineering and manufacturing don’t have the shiniest kind of reputation as careers, purely because they give people the impression that it still mostly involves working in factories, which seems old-fashioned and unattractive. People generally don’t realise what these businesses are really like now.

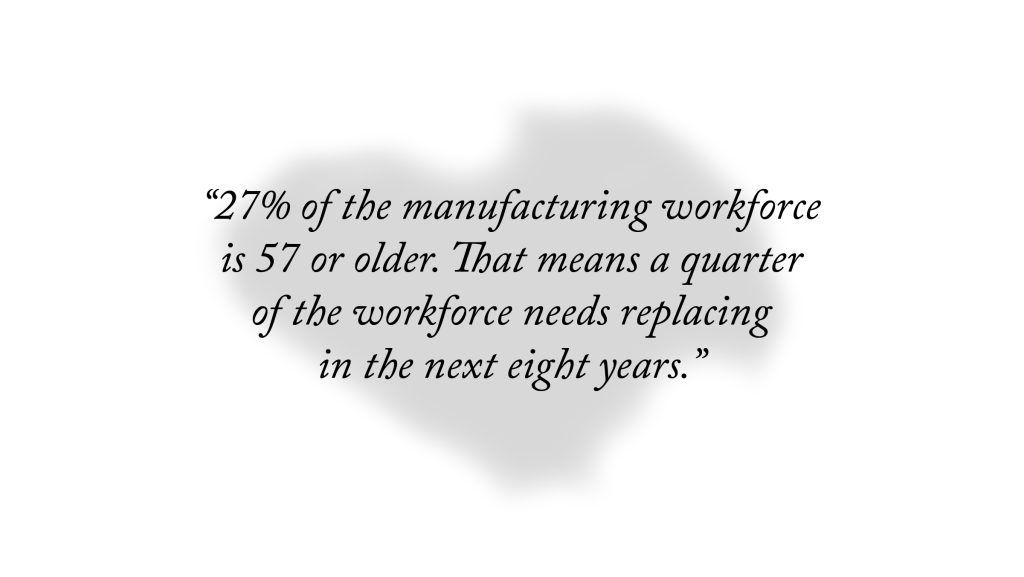

Esther: I agree, the industry hasn’t got the best reputation and isn’t attractive for younger people, who tend to think of it as being dirty and dangerous and altogether outdated. In reality that’s not the case. Many of these businesses are high tech, advanced in digitalisation, often pioneers in using AI. But the reputation hasn’t caught up with the reality, and the old-fashioned image persists. At the same time, 27% of the manufacturing workforce is 57 or older. That means a quarter of the workforce needs replacing in the next eight years. The risk is that vital knowledge will leave with those older workers, resulting in skills shortages, a dampening of innovation, and that all adds up to more reputational problems.

Lindsay: Is the answer for manufacturing and engineering to embrace the fact that they need to tell these stories, to reach out to younger and more diverse audience?

Michelle: First, there’s that lack of clarity about what exactly the manufacturing sector is. There are a lot of sub-sectors, which people don’t really think of as part of manufacturing. A lot of people will just say, ‘Oh, I want to work in technology’, but maybe they never realised that the jobs they’re interested in are actually part of the manufacturing sector. We spoke about diversity and inclusion earlier, and I think gender equality is crucial here. The industry is still very much male dominated, and more needs to be done to appeal to girls and women, to bring their skills and talent into manufacturing.

Esther: Agreed – not having that balance I think is potentially dangerous, not just for the manufacturing companies, but for society as a whole. Manufacturing is crucial for the world economy, not just for the UK, it’s a global industry. Companies can look internally first. If there is an opportunity to run training programmes for people who are already in the company, that up-skilling or re-skilling can enable them to fill a specific role that’s missing.

Michelle: I also think it can be more important to find the right person, and then develop their skill, rather than look for someone with a specific skill. It can take forever to find the right person, someone who has the right skills and fits in your team, fits in with your company culture. As the old saying goes, ‘hire for fit, train for skills’. Because an existing employee who’s been given the training, given the chance to develop, could become an influencer, they could become a brand ambassador from that point on. Even if they just spread the word among their friends, that could have a positive influence on the image of the company and of the sector as a whole.

Lindsay: Doesn’t that also imply a need to be aware of the different skills you’re buying when investing in younger talent? Can you do that as a leader of a certain age, as leaders tend to be, can they really identify what young hires can do?

Esther: Well, one thing leaders can do is ask young people! It’s something we do a lot at GW+Co, helping businesses to recognise the potential in their people through collaborative design processes, instead of relying on assumptions and stereotypes or the latest AI tool or whatever. But asking applies to people of all ages, including the ‘detired’ – people enticed out of retirement to fulfil specific needs because of their experience. Instead of tailoring the employee value proposition by generation, it’s more worthwhile to take action on the factors that all the research shows employees actually want – fair compensation, opportunities for career development, caring leadership, flexibility, and meaningful work.

Lindsay: The trick is to do that while appreciating the nuances of life stage, personal circumstances, and individual preferences. But surely it has to be based on principles, not personality?

Michelle: Yes, as Simon Sinek says, good leaders don’t care about who is right, they care about what is right.

See you next time!

What’s next?

Want to know more about GW+Co? Have a chat with Olivia

Have a question? Ask a question of one of the authors – Michelle or Esther

Have a strategic problem? Walk with Gilmar